Update, May 10, 2023, at 10:44 a.m.: This story has been updated to reflect the charges prosecutors announced against Santos on Wednesday.

New York Rep. George Santos’ career in Congress is only in its fifth month, but already he’s taken up an outsize presence in Americans’ psyche—due to his résumé embellishments, his district’s voters wishing he would quit, his Botox use, his introduction of, er, a normal tax bill, and more.

But perhaps the largest segment of Santos reporting (at least 30 articles’ worth in the Daily Beast, Mother Jones, Washington Post, New York Times, and other publications) is about what one might describe, delicately, as his uniquefinancial situation and record of curiouscampaign expenditures.

Advertisement“When it comes to Santos’ campaign, you can shatter your brain trying to find the logic or reasoning behind many of his maneuvers,” said Brendan Fischer, the deputy executive director of the watchdog group Documented. “When looking at questionable activity by an experienced candidate, you can usually figure out what law they are trying to skirt and why they’d want to engage in a particular course of conduct. But some of Santos’ campaign activities just seem to be unexplainable.”

Now Santos faces a host of federal charges over his financial activities, including stealing public funds, money laundering, and lying on federal disclosure forms. He is accused of using fraudulent means to bring in campaign contributions, and of spending them improperly (among other things, to buy designer clothes and make his car payments). Authorities seem interested, in particular, in digging into his self-reported wealth.

We’ve tried our best to untangle that mystery—where did Santos’ money really come from? The story includes Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the cousin of a Russian oligarch, and a yacht.

AdvertisementIn campaign-related filings, Santos claimed to have made at least $3 million, personally, in the two years before he won his election. He also reported raising just under $3 million for his campaign from various sources, with his campaign reporting that it spent more or less all of the money it raised.

Advertisement Advertisement AdvertisementA rich guy spending his way into Congress is, of course, the American way. But this is not necessarily your average rich-guy-running-for-Congress scenario.

What, for example, was Santos doing to make $3 million in the years leading up to his win? Santos’ known or alleged streams of personalincome during the period in which he ran for Congress included:

● Compensation for his work at a company that’s been accused by the Securities and Exchange Commission of operating as a Ponzi scheme.

Advertisement● Payments received by companies he founded with co-workers from the firm that operated the alleged Ponzi scheme.

● Revenue generated by a company he founded by himself that doesn’t have any other known employees—and whose nature and business model he has described in inconsistent and confusing terms.

As for the other $3 million, the Santos campaign’sself-reported sources of funding included:

● A loan from Santos himself (using proceeds, Santos says, from his own business, whose function he has described in inconsistent ways).

● Individual contributions from people who reportedly now say they never donated to Santos, or who appear not to exist.

● Donations solicited by a staff member who was allegedlypretending to be someone else.

His campaign’s self-reported expensesinclude:

● Payments that don’t appear to have actually been made.

Advertisement Advertisement● Payments that almost certainly could not have been made in the amounts the campaign claims.

● Payments that were listed as having been made to “anonymous.”

One thing that is particularly curious is how dramatically Santos’ financial situation has seemingly improved in recent years. In 2020 he ran for Congress and declared that in the preceding year he had been paid $55,000 by a company called LinkBridge, which holds conferences for investors. He lost that race.

In 2022 he ran for Congress again, hammering on complaints about inflation and relentlessly touting his alleged respect for law enforcement. This time, he declared that he had earned $750,000 in salary and between $1 million and $5 million in dividend income from his own company, the Devolder Organization, in 2021 (and then earned the same amounts in dividend income in 2022). He also claimed that he had loaned $705,000 of his own money to his campaign and raised $1.5 million from individual donors.

Advertisement AdvertisementWhat does his company do? Appropriately, given that it sounds like a shadowy entity from a prestige television series set in a dystopian near future, it’s unclear what business the Devolder Organization was in. Santos said in a December interview with Semafor that it was a “capital introduction” company and described himself as a sort of free-floating broker who arranges transactions between wealthy people. But in the financial services industry, “capital introduction” is a term with a specific meaning that applies to services performed by large institutions, not one-person firms.

Advertisement AdvertisementThe Santos campaign website, by contrast, at one point said the Devolder Organization was actually a family investment fund at which he oversaw $80 million in assets. But Santos does not appear to have come from a wealthy background; his mother listed herself on immigration documents as a housekeeper, while he and his sister have both been the subject of eviction proceedings in the past.

AdvertisementWhatever it is, the Devolder Organization is currently registered at the address of a Fast Mail N More store in Melbourne, Florida. It looks like this:

In a late December scoop, the Daily Beast reported that the Devolder Organization did have at least four clients—three businesses and a not-for-profit with connections to individuals who had also donated to Santos’ 2022 campaign. Those individuals included a Long Island auto-dealership magnate named Raymond Tantillo; the wife and children of a Miami-based lawyer and health insurance entrepreneur named John Ruiz; and an insurance executive named James Metzger, who was once described by Social Life magazine as “Long Island’s Leading Lacrosse Benefactor” (probably a competitive philanthropic niche, actually!).

AdvertisementNeither Metzger nor any members of the Tantillo or Ruiz families have commented publicly on what services the Devolder Organization performed for their organizations; Slate’s inquiries to Metzger, Tantillo’s company, and a spokesperson for John Ruiz went unreturned. (A lawyer for Ruiz previously told the Times that Ruiz “does not know who George Santos is and has never contributed to his campaigns and has never done any business with him.”) None of Santos’ donors or clients have been accused of violating the law in their dealings with him.

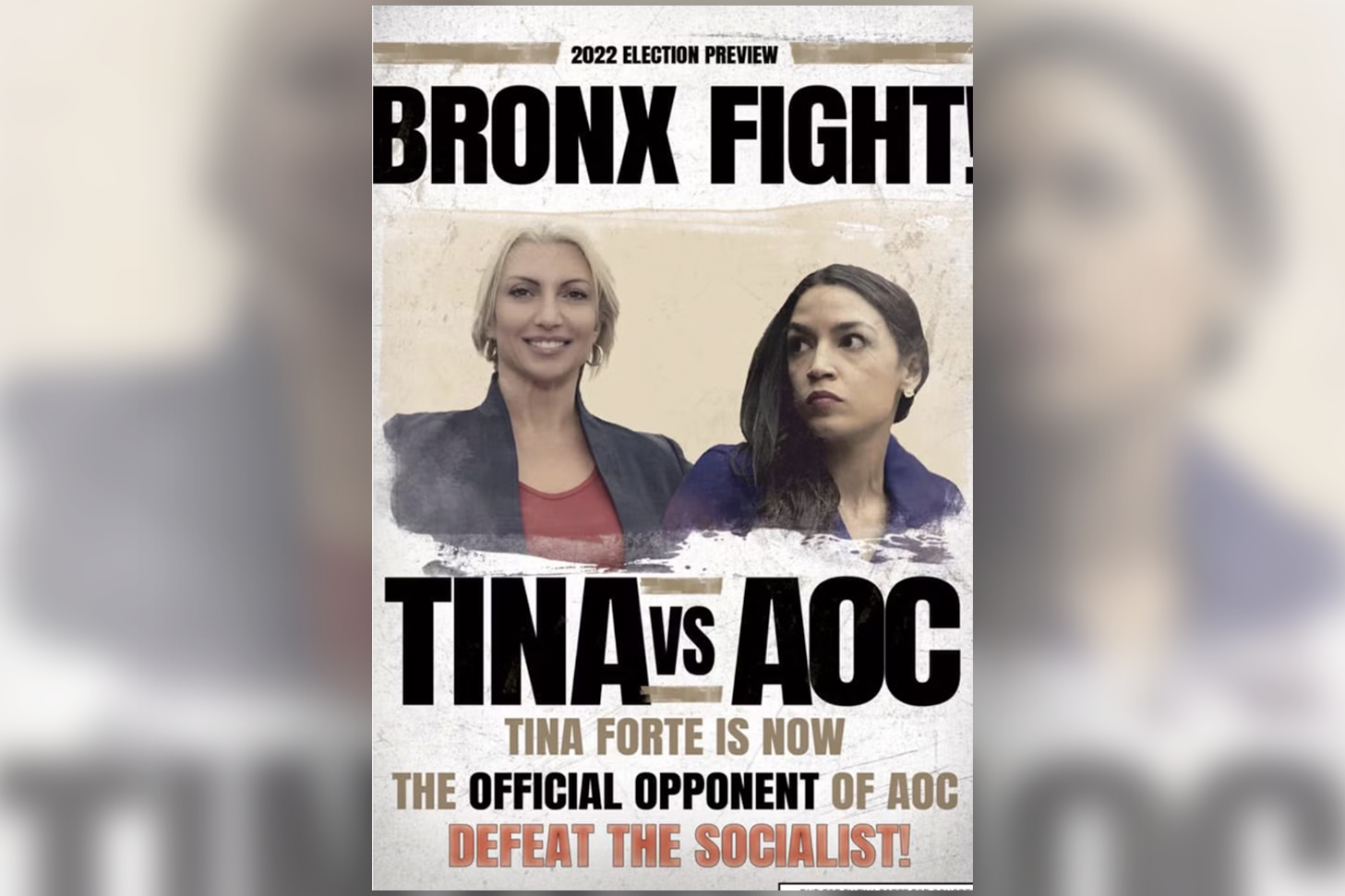

AdvertisementSantos’ other reported sources of revenue are equally … hmm … quirky. Among them: the company involved in the alleged Ponzi scheme—Harbor City Capital—and the company founded with alumni fromHarbor City Capital that helped a brassy Italian American named Tina Forte raise $1.5 million to run against Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in 2022. (Forte lost the race by 43 points.)

Advertisement AdvertisementHarbor City Capital advertised itself on its website in 2020, according to the Wayback Machine, as a “global alternative investment” firm. Its tag line: “A Safe Harbor To Grow Your Wealth!”

In an interview on a website called Superbcrew.com, the founder and CEO of Harbor City, a self-styled entrepreneurship guru named J.P. Maroney, said he could guarantee results for clients by “implementing strategies that generate reliable yields from the Internet advertising sector.” (As a writer for a digital media site myself, I am skeptical of how large or reliable these yields might be, but I digress!) He said his “entrepreneurship journey started at age 19” and predicted that the next few years at Harbor City would be “an exciting ride.”

Advertisement AdvertisementThat same year, 2020, Santos was announced as the company’s “New York regional director.” (He was going by the name George Devolder at the time, a fun twist that makes things extra confusing.) In a press release that announced his hiring and his mission of “expanding Harbor City Capital Corp in the private wealth sector,” Maroney praised Devolder for the way he “conducts himself in business.”

AdvertisementIn April 2021, though, Maroney and the company were accused, in a lawsuit filed by the SEC, of operating as a Ponzi scheme, i.e., paying “returns” to initial investors using deposits made by subsequent investors. (Among other curious details, the SEC’s filings reveal that the company, over the course of its existence, deposited a total of $426,000 into the National Bank of Uzbekistan.) The only employee of Harbor City accused specifically of wrongdoing by the SEC was Maroney himself. Santos/Devolder has denied having had any awareness of the alleged scheme. The SEC’s litigation against Maroney was stayed in October 2022, after he informed a judge that he, Maroney, is also the subject of a “related criminal investigation.” He currently lists himself on LinkedIn as a “Fractional Chief Marketing Officer” who is available for hire. His public Instagram account features a lot of motivational sayings about business, alongside the hashtags #MakeMoney #MakeMemories #MakeADifference.

Advertisement Advertisement AdvertisementView this post on Instagram

While at Harbor City, Santos reportedly managed the account of at least one investor, a New Yorker named Andrew Intrater, who purchased $625,000 worth of the securities the company was selling. Intrater, who happens to be the cousin of a Russian billionaire who’s been heavily sanctioned by the U.S. government, appeared in news stories in 2018 because his business had retained the services of onetime Trump lawyer Michael Cohen. The business paid money to the same paper company that Cohen used to pay Stormy Daniels to secure Cohen’s help in finding “potential sources of capital and potential investments.” Intrater, who was never accused of any crime related to his payment to Cohen, also later became a donor to Santos’ congressional campaign.

Advertisement AdvertisementAfter the SEC filed suit against Harbor City in 2021, Santos and four other individuals formerlyemployed by the firm set up some companies. One was called Red Strategies USA; another, RedStoneStrategies (emphasis mine).

The only public indication that Red Strategies was ever an active business is a disclosure that it was paid $110,000 for “digital consulting and fundraising” by Tina Forte, the aforementioned Republican who ran against Ocasio-Cortez in 2022 and lost the general election by 43 points. Forte campaigned hard on the idea of taking down AOC; one image on her campaign Facebook page, for example, positioned the election as a boxing match. “Bronx Fight!” it screams. “Tina Forte Is Now the Official Opponent of AOC. Defeat the Socialist!”

AdvertisementForte attacked Ocasio-Cortez for—among other things—being soft on crime, a charge that is perhaps somewhat hypocritical given that Forte’s husband and son are, according to the Daily Beast, both multiple-time felons whose convictions include charges related to a 2019 drug bust at the family’s beverage distribution center in the Bronx. (Forte’s son pleaded guilty to a weapons charge related to that incident, while her husband pleaded guilty to conspiracy to distribute marijuana.)

No matter!

One common link between Forte, Santos, and Red Strategies was a longtime Republican operative named Nancy Marks. Marks was Santos’ 2020 and 2022 campaign treasurer, and for a time she was Tina Forte’s 2022 campaign treasurer as well. She was alsoa co-founder of Red Strategies.

Advertisement AdvertisementAs Mother Jones and the Daily Beast have documented, Marks also served at various points as the treasurer for two otherRepublicans who competed in the 2022 primary to run against Ocasio-Cortez. (This was the primary Forte eventually won.) For a period, Marks was the treasurer for both Forte and another Republican in the same primary race—at the same time. And in 2020, she was the treasurer for John Cummings, the Republican who won the nomination to run against Ocasio-Cortez in thatcycle. His campaign paid Marks $10,000 a month (via another one of her companies) for “strategic political consulting services” through December 2022—more than two years after his campaign ended in a 44-point loss. Cummings’ campaign is actually stillsubmitting expense filings—it paid the email management company Constant Contact in February 2023. Marks’ home in Shirley, New York, is listed as the Cummings campaign’s address.

AdvertisementThis is all confusing and intertwined, yes. Which is why it may be useful to remember here that Ocasio-Cortez, since winning election to the House in 2018 for the first time, has become a right-wing obsession. Her most minor moves are clocked and criticized around-the-clock on right-wing television and radio networks, and her name has become something of a boogeyman catchall for any perceived problem associated with liberals or progressives. Which is to say: Candidates running againsther have a rich vein of animosity to tap into for fundraising, even if those candidates have almost no chance of winning.

Advertisement AdvertisementAn anonymous quote in a Feb. 16 Daily Beast article—attributed to someone who worked on Santos’ extremely unsuccessful 2020 attempt to force a recount of his race—tries to connect the dots between Santos, Marks, and Cummings, Ocasio-Cortez’s long-shot opponent from 2020:

Advertisement[There was a] big explosion of money coming through outside network people, and George wanted in. George didn’t understand why John was raising so much more money, and he was always trying to get at email lists from John. And then later George got Tina Forte to run for that seat and assumed he could control information on fundraising from the AOC district, whether it was from direct mail or email lists.

It’s not clear, for the record, how Santos “got” Forte to run. When Mother Jones reached Forte for comment, she told the publication “she was too busy making marinara sauce to talk.” (Not joking.) Marks did not respond to a phone call and an email from Slate, and Forte did not respond to multiple messages.

AdvertisementBoth Red Strategies and Santos’ other company, RedStone Strategies, were registered in Florida. RedStone Strategies doesn’t appear to have a public presence, but the New York Times has reported that individuals purporting to work for a not-for-profit political organization called “RedStone Strategies” solicited money from Republican donors to support Santos during the 2022 campaign. To be clear, there appears to be no registered political organization called RedStone Strategies—just the for-profit business in Florida.

Advertisement AdvertisementHowever, the Times says that the solicitors, whomever they worked for, seem to have succeeded, in at least one case, in receiving a donation for $25,000—from Andrew Intrater, the Harbor City client with the Russian connection. There unfortunately isn’t any record of what happened to the $25,000 once it arrived in the bank account where Intrater says he was told to send it. Intrater donated what he says was more than $200,000 in total, through various groups, to support Santos’ 2022 campaign.

Advertisement AdvertisementRecall that Santos previously invested Intrater’s money through Harbor City, and that Intrater’s cousin is a Ukraine-born Russian billionaire. That man’s name is Viktor Vekselberg. Vekselberg controls an industrial conglomerate called the Renova Group and is often described as an ally of Vladimir Putin. Intrater operated a U.S.-based company that “managed assets” for Vekselberg before Vekselberg was sanctioned.

Neither Intrater nor Vekselberg has ever been accused of having engaged in illegal activities related to Harbor City or the Santos campaign. For his part, Intrater told the New York Times that he is winding down his financial connections to Vekselberg and has not had “business dealings” with his cousin since sanctions were issued against him. Intrater also said that he believed that Harbor City was a legitimate business, and that he continued to support Santos politically after the SEC accused Harbor City of operating as a Ponzi scheme because he believed that Santos was one of Harbor City’s victims—not a participant in its fraud. (Intrater declined a request from Slate to comment further.)

Advertisement AdvertisementIntrater is far from the only Santos donor—or alleged Santos donor—who has reason to be unsure about what happened to their money once it made its way (or allegedly made its way) into campaign accounts. Here’s a list of the problems that journalists and watchdog groups have identified in Santos’ campaign filings:

Advertisement• The campaign reported that Santos personally loaned it $705,000. As discussed above, there are reasons to wonder how someone like Santos, who did not have a distinguished professional record and gave inconsistent explanations of what services were performed by the business from which he claimed to have derived significant personal wealth, could have come to possess that amount of money. (In January, the campaign filed amended forms that don’tlist those contributions as personal loans, but do not otherwise offer any clarity about where the money came from.)

Advertisement• The campaign reported an extraordinary number of expenses totaling exactly $199.99, which is 1 cent less than the amount for which the Federal Election Commission requires the submission of a receipt. Seven of these $199.99 payments were made to an Italian restaurant in Queens owned by a man named Joseph Oppedisano. Santos’ campaign reported spending more than $40,000 in total at Oppedisano’s restaurant; both Oppedisano and his brother Rocco, an Italian national, donated to Santos’ campaign, while Santos named Oppedisano’s daughter Tina to his small-business coalition. There is a lot to learn about the Oppedisanos that has nothing to do with Santos, including the fact that Rocco was once described by the 2ndU.S. Circuit Court of Appeals as having “an extensive criminal record,” which includes a 2012 conviction for possessing ammunition that was discovered during a search of a home that Joseph told the Daily Beast that he owns. (According to court documents, Rocco was staying there at the time; Joseph was not implicated in the case.) Rocco would go on to be discovered by the Coast Guard 2 miles off the coast of Florida on a yacht on which authorities also found 14 undocumented immigrants and “$200,000 in Bahamian and US currency,” which was hidden behind the wall of a bedroom. The next year he pleaded guilty to a related charge of bringing undocumented immigrants to the United States for financial gain. Santos has not been implicated in any of Rocco’s criminal activity, although his campaign likely violated the law by accepting a donation from a foreigner. He seemed to like the Oppedisanos’ restaurant, though, posting on his Instagram page that Il Bacco was one of the district’s “most remarkable local businesses.” (My colleague also visited the restaurant in January, to understand its appeal.)

Advertisement Advertisement Advertisement AdvertisementView this post on Instagram

• The campaign claimed to have made a total amount of payments to the Republican fundraising platform WinRed that was reportedly more than six times as large as what it should have paid. (To explain: WinRed charges campaigns a fixed percentage of what they raise using its platform. The Santos campaign raised about $800,000 through WinRed, according to WinRed’s numbers, which would add up to about $33,000 in fees. But the campaign reportedpaying about $206,000 to WinRed instead. WinRed told NBC News it had “proactively reached out to the campaign to ensure its agency fees were being reported accurately.”)

• The campaign listed more than $250,000 in expenses (including many expenses for $199.99) as having been paid to “Anonymous.” It then amended those filings to list those payments as not having any specified recipient at all. (Ultimately, more than $365,000 in Santos expenses remain listed without a recipient.)

Advertisement• The campaign reported making payments to an entity that appears to have owned the home where Santos was living—i.e., paying rent. (Campaigns can’t pay personal expenses.)

• The campaign employed a fundraiser who allegedly told donors that he was now–Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy’s chief of staff but was not. (LOL.)

Advertisement• The campaign reported donations from individuals who either reportedly don’t exist; told reporters they never actually gave money to the campaign; or, in one case reported by Talking Points Memo, said they didgive money to the campaign but later found that their credit cards had been charged repeatedly for other donations they didn’t authorize.

• And the campaign claimed to have made donations to other Republican campaigns and groups that have no record of having received them at all.

AdvertisementThis last detail particularly inflamed Brendan Fischer, the campaign finance expert. “This one is very hard to explain. If you’re going to try to hide where your campaign money is going, then don’t leave an obvious paper trail. Why claim to have contributed to another political committee that has to report its receipts? It just boggles the mind,” Fischer said.

AdvertisementAccording to a late January Washington Post report, the Department of Justice asked the FEC to pause its investigation of Santos, indicating that a criminal probe of his activities was underway.

OK, that is a lot of information. Are we any closer to understanding what’s going on here, in terms of where Santos is getting his money and where he is sending it?

Advertisement Advertisement AdvertisementThe New York Times delivered what is perhaps an important piece of the puzzle on March 15, reporting that Santos had, in fact, brokered the sale of a $19 million yacht between two Devolder Organization clients. The paper also reported that “several donors have described encounters with Mr. Santos at fundraisers in which he would describe deals he could broker with other donors.”

That’s still not really “capital introduction” as other finance professionals would define it, and the paper also reported that “none of the other potential arrangements described to The Times appear to have resulted in deals.” But it starts to make some thematic sense when paired with the Daily Beast’s reporting about Santos and his close associates from the anti-AOC contingent, which certainly appears to be a rich vein of, well, money.

AdvertisementSantos, it seems, realized that a great deal of cash could be raised online from small donors in this current political environment. He also seems to have used campaign events to mingle with big fish, pitching them on his potential value as both a congressman and a guy to know in the world of finance.

Federal laws prohibit the transfer of corporate funds—like those that would have been paid to the Devolder Organization for brokering yacht transactions, or to Red Strategies or RedStone Strategies—to political campaigns. That’s true even if the money is routed through to an individual, or—hypothetically speaking!—given to the campaign under the name of someone else. Simply put, the law says you can’t use a business transaction or a third party as a means of getting money to a candidate that you wouldn’t have been allowed to give to that candidate directly. (There is no evidence that any of the individuals or entities named by the Beast or the Times who paid the Devolder Organization, Red Strategies, or RedStone Strategies were attempting to intentionally circumvent campaign finance laws.)

Advertisement AdvertisementFederal laws also prohibit the use of campaign funds for personal expenses.

The question still remains: If Santos were trying to mix politics and business to advance himself personally in a way that was at least tricky from a legal standpoint, why would he have left so many “please investigate me” red flags in his campaign filings?

To paraphrase Fischer, the campaign finance expert: At some point, you have to stop thinking about what a financial mastermind would do and start thinking about what George Santoswould do.

Advertisement“Campaign finance laws are ridden with loopholes and dangerously under-enforced, so there are tons of ways that wealthy donors could secretly support a politician above and beyond legal limits,” Fischer said. “But your average wealthy donor is going to give where the candidate asks them to give. A small handful of megadonors who have their own political team might start a super PAC of their own accord, but usually donors are following the candidate’s lead about where their money should go.”

Advertisement AdvertisementIn 2022 Santos had the credential of having won a Republican nomination for office before, and he was able to present himself as a financial and political insider in a way that fooled a lot of people. It’s not implausible, Fischer said, to believe that donors, even experienced ones, would take his word for where to send money to support him.

Advertisement AdvertisementBut he was, in reality, a relatively unknown and inexperienced political figure. He doesn’t appear to have had a large legal team or gotten much support from the national Republican Party. He may have lacked the sophistication or organizational resources to manage the money he got his hands on.

Since it was first reported in December that large parts of George Santos’ résumé were fabricated, the saga of the freshman representative has become one of remarkable scope. Even the smallest details of his life are hard to pin down. He has been accused of lying about having worked at Goldman Sachs and Citigroup; about having Jewish grandparents who fled the Holocaust; about his mother dying in the attack on the World Trade Center; and about being a star volleyball player at a college he didn’t attend. Brazilian authorities have investigated him for allegedly buying clothes with a stolen checkbook; a former roommate says Santos stole his scarf and wore it to the Capitol riot on Jan. 6; a veteran in New Jersey accused Santos of stealing thousands of dollars from a GoFundMe account that was meant for a lifesaving surgery for his dog. There’s a lot more.

Advertisement AdvertisementSantos—though he admits to having embellished his résumé—has denied ever stealing from anyone or committing fraud. But he has in fact been accused, many times, of taking things of value from other people and using them in ways he wasn’t supposed to. And it is hard to believe that his campaign was acting legitimately when it reported a huge series of payments for precisely $199.99, or claimed to have received donations from people whose existence cannot be confirmed. (Santos’ congressional office forwarded questions about the matters discussed in this piece to his attorney, who declined to comment.)

AdvertisementPopular in News & Politics

- A Supreme Court Justice Gave Us Alarming New Evidence That He’s Living in MAGA World

- Ten Years Ago, His Book About Civilizational Collapse Got Unexpectedly Popular. He’s Back With a Little Bit of Hope.

- We’ve Been Entertaining an Illusion About the Supreme Court. It’s Finally Been Shattered.

- Them Supreme Court Boys Are at It Again

By cobbling together personal connections and bits of money, adopting the personal style of a finance and technology big shot, and repeating culture war phrases about woke indoctrination and “backing the blue,” he became the Anna Delvey of the political world—faking it with such commitment that everyone assumed he had really made it, at least until he got elected. (Delvey was a Russian immigrant who became part of New York high society by more or less showing up and acting as if she belonged, as well as by committing some light financial fraud.)

So while it’s not always clear what Santos is doing, it’s clear how he wants to be seen, which is as a well-connected man of influence. And isn’t he one? Say what you will about him, but don’t say that he isn’t a member of Congress who arranged the sale of a $19 million yacht! A confidence man, after all, has to know what the rest of society thinks a successful and trustworthy person looks like. Wherever George Santos’ story goes next, it already tells us a lot about where we’ve been.

Tweet Share Share Comment